The North Sea had seen several companies involved in oil exploration during 1971 and 1972. The discover of huge oil wells was heralded as the saviour to the UK economy. While Government Ministers hinted at free petrol and cheap heating others were eyeing up ways of getting the black stuff out of the wells and into refineries. Within a very short period, oil rigs had been placed in the deep icy waters off the Shetland Islands and work was soon to begin. The next logistical headache the oil companies faced was how to get the workers onto the rigs. Helicopters would be the obvious choice, but the distance from the mainland and the helicopter's range limitations ruled out direct flights. Another consideration was the hellish weather conditions that often prevailed in the region. A more practical solution would be the use of fixed wing aircraft carrying out the bulk of the work from the mainland to the nearest airport with runway facilities. The Shetland Islands had just one airports at the time, Sumburgh. Much later on Wick airport was opened. The Sullem Voe oil terminal was opened later on and Scatsa Airport was the natural choice. Flights could fly the 167 miles from Aberdeen to Sumburgh in ninety minutes. Dan-Air had been involved in 1969, during the early oil exploration days. An Ambassador aircraft had carried out a series of charter flights to Aberdeen from Norwich Airport.

Airlines in the UK smelled the whiff of opportunity and submitted various applications to carry out these new charter flights. Some companies, such as Air Anglia wished to carry out flights using a sole DC3 Dakota. Loganair, the Scottish regional airline was a natural choice. They had a heavy presence in the area as one would expect. Their fleet however was woefully inadequate for the anticipated flow of oil workers. British Midland Airways had a small fleet of Vickers Viscount aircraft, and British Island Airways the Herald. Dan-Air had recently acquired the Hawker Siddeley 748 following their take-over of Skyways, but they were heavily involved in the airline's 'Link-City' network and the popular London-Paris coach air programme. British Airways believed they would be the obvious choice for the flights as they already had a fleet of helicopters.

Dan-Air took delivery of further HS 748 aircraft. Negotiations between the airline and the Conoco Oil Company resulted in Dan-Air being awarded the contract to carry oil industry workers between Aberdeen and Sumburgh. The led to a single HS 748 being based at Aberdeen Airport full-time in June 1974.

Ironically there was a fuel shortage at Aberdeen Airport that same month, with Sumburgh being in possession of more aircraft fuel than their mainland counterpart. This led to problems with Air Anglia and Loganair, whose piston engine aircraft used Diesel fuel. Airport chiefs had ruled that that particular fuel should only be used for air ambulance and air rescue flights, forcing the airlines to sub-charter aircraft from British Midland and Dan-Air. In May, Loganair's tiny aircraft had carried more than 500 passengers, a record for in a single month. Sumburgh had seen a new record of 97 flights in a single day. Bristow Helicopters, who would take the passengers directly onto the rigs carried out 32 flights in a single day. British Midland even submitted applications to operate scheduled flights into Sumburgh.

This instant boom in traffic had meant almost every UK airline had been approached to carry out oil supply charters. Skyways had been awarded a contract to fly DC3 aircraft between Aberdeen and Sumburgh. The oil company wanted the aircraft to carry up to 20 passengers and cargo. Dan-Air's subsequent take-over of Skyways saw another contract fall into their lap. The ageing DC3 was replaced by a HS 748 which had the cargo capacity and could carry more than double the passengers. The aircraft could not have performed better. Its sturdy, rugged design was able to land in hostile weather when other aircraft were grounded. The small fleet of 748s even managed to carry oil workers to a rig off the coast of Oporto in Portugal during 1974 and 1975.

The airline stated that some airlines had prospered on the oil supply charter market and others had failed. Dan-Air's own success, they believed, was a result of them being a large airline and choosing the Hawker Siddeley 748 to carry out the flights. The aircraft had a low landing speed and excellent crosswinds capability. This, they said, gave the aircraft regularity in the harsh weather conditions in the north of Scotland. The aircraft could be converted from a passenger airliner into an all cargo layout in under 45 minutes. For this, Load Masters were employed who had been specially trained in storage of freight. Dan-Air wished to offer passengers a high standard of service and exacting standards with the oil supply division. Something that no other airline came close to providing.

Dan-Air submitted plans to operate scheduled flights from London Gatwick to Aberdeen with the hope of attracting oil workers who travelled from further afield than Scotland. Many of whom would be in senior management positions. This would mean that a base would need to be opened in Aberdeen, where full-time staff would be employed. As the oil supply flights became more regular in 1976, a base would open at Sumburgh itself along with a small engineering department.

By 1976 Dan-Air had in fact, opened an office at Sumburgh Airport, although Loganair would handle their flights. In a very short time Dan-Air were by far the largest provider of oil supply charter flights, which necessitated the purchase of a third HS 748 aircraft, which would be permanently based at Aberdeen. Pilots would not be permanently based at Sumburgh, they would instead take it in turns to be stationed there for eight day stretches, where they would fly daily from Sumburgh to Glasgow and back again. They would also be required to fly to from Sumburgh to Aberdeen, and sometimes to Bergen in Norway. In all three cases the flights were operated on behalf of Shell.

As the labour force at Sullem Voe grew, so did Dan-Air. A new contract with BP was signed and three HS 748s would be based at Sumburgh for 1977, in addition to the ones at Aberdeen. The airline announced they were looking for local girls to train as air hostesses. In August two of the airline's HS 748s burst tyres on landing, it was explained that they had made exceptionally hard landings due to thick fog.

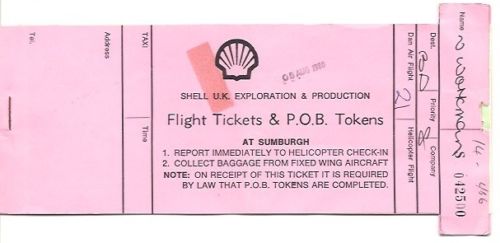

Dan-Air's oil supply charters had almost turned into an airline of its own. These charter flights differed from regular charters in that there would be little emphasis on selling products such as duty free or drinks to the passengers. Workers on the oil rigs had to forego alcohol for the entire time they were stationed. Cargo would also be carried, which regular charters were not permitted to do. Bristow and British Airways helicopters by this time built up a fleet of more than twenty aircraft to carry out the final stage of the journey. Robin Duke of Shell told us:

'We had been operating the charters for some time and it had been a bit of a headache to get the CAA to approve passenger and cargo charters. They were used to applications for charter flights of course, and these may well have been cargo flights. But most UK charters were to holiday destinations and they were forbidden from carrying any cargo, other than passenger luggage of course. We would sometimes require equipment to go from the mainland to a rig. It would not be huge, because the helicopters that carried out the second leg of flights were not large enough. We had a hell of a job getting them to accept that we these flights were exceptional and had to be treated differently. We were not trying to con them in any way, they finally accepted that rather than charter two flights one for passengers and one for cargo, that it would make sense to combine the two.'

During an exceptionally cold January in 1977 a company HS 748 suffered a broken undercarriage and damaged propellers. Dan-Air's Sumburgh base manager Ken Shield said: 'The weather was pretty grim. What happened was that it simply slid off the end of runway at the end of its run.'

The accident attracted attention from airport worker (images: Gerald Flaws)

Dan-Air were well aware that should they acquire more aircraft, they would be certain to obtain more contracts. As a substantial airline, senior management had many contacts and it was discovered that three HS 748 aircraft were available to purchase in Argentina. It was disclosed in the press that the aircraft had been purchased for a giveaway price and that they were not in the best of health. One of our engineering contributors told us:

'We were given instructions, along with several flight crews, to fly to Argentina and inspect these aircraft, which we knew might not be airworthy. We would use a company aircraft out of season, which would have lots of the most obvious spare parts and fly to Argentina. We would be given assistance in making them airworthy. I'm not entirely sure if the aircraft were inside the airport perimeter or out of it. In any case they had been allowed to be used as a chicken coop. I cannot describe the smell. There was chicken shit on everything. Including the flight deck controls. That was the first task. Cleaning all that shite took us several days. We had no idea what we know today, that bird faeces us carcinogenic, and we just went about scraping it up and washing it off without even a mask on. After that, we did the most basic of stuff, you know, oils, hydraulic fluids and fuel. To our astonishment, the aircraft started up first attempt. It was clear that they had issues though. We knew that once we got them back to Manchester, we had all the tools to make them as good as new. The problem was how to fly them safely over such a long distance. The Argentinians had been using them for different jobs than what we would be using them for and they had no heaters in the flight deck. The flights back were freezing. All of those pilots who had agreed to fly them back were very brave I felt, but they had so much faith in the type. I think there were seven of them in this deal, and they were almost giving them away. Most airlines would not have decided that it was worth the risk or the time and effort to get them up to CAA standards. I didn't work in finance, so I don't know the figures, but I suspect it worked out in Dan-Air's favour. As far as I remember, the heaters were not replaced and crew were always complaining about how cold they were when they were in the Highlands. The end of the story is that they did all arrive safely in the UK. The maintenance that had been done when they were in service with the Argentinian airline was questionable, and a result we lost one of them in an accident in Sumburgh. That was as a result of the gust lock device having parts changed that were not manufacturer approved. It was not something that could be seen during normal maintenance.

At Manchester there was a lot of work to be done. Even parts of the aircraft that were covered were found to have chicken crap on them. But they eventually entered service. I later heard that some of the electrical looms had shorted in flight. Passengers had noticed that their feet were getting very warm! Some of them had fused together and it was lucky that they hadn't set alight.'

It was rumoured that the cost of bringing the aircraft up to UK specifications would be £2 million, which was considerably less than purchasing seven new aircraft. The delivery flights home would see the aircraft fly north to Mexico, the Caribbean, North America, Canada and then across the Atlantic with stops at Iceland and Ireland before landing at Lasham. Their final leg was to Manchester where they would undergo extensive maintenance to enable them to join the UK register and thus the Dan-Air fleet.

One of the workers at Sumburgh recalls a frightening incident in 1977:

'A batch of A1 Jet fuel was found to have been contaminated with water when it arrived at Robertson's Lerwick depot. We had hoped that the decent weather we'd been having might have helped evaporate the water through condensation but it didn't. That was on the Friday, by Sunday we were almost out of uncontaminated fuel. It didn't really affect fixed wing aircraft, it was the helicopters. We had to keep some aircraft fully tanked up at Sumburgh in case of emergency, so all the flights that weekend had to go out of Scatsa in Wick. It wasn't as well equipped as Sumburgh. It was a nightmare. Dan-Air came up with a solution, they would fly their flights to Bergen in Norway and Bristow re-positioned some of their helicopters there. I was impressed at that. No other carrier did it. I think that might have affected the oil companies decisions about who they would use when contracts were up for renewal.'

The end of 1977 saw a problem with Shetland's airports that could never have been predicted. The airports were close to full capacity during their opening hours. Bosses at the airport said that there could be up to a third of flights scheduled to arrive in 1978 would be refused permission. The full details were revealed by the Civil Aviation Authority's UK Off-Shore Operators Association. The idea of rationing flights had alarmed members of the community and the local council was forced to announce that any limitation of flights would not affect any flights carrying scheduled passengers. The council admitted that the level of expansion in the Shetland basin had been 'astounding'. When the oil supply flights had first commenced in March 1974 it had been predicted that there would be 18,000 flights a year by 1980. That figure had been exceeded by 4,000 in March 1975. The following year there had been 24,694 movements at Sumburgh. The authorities were now predicting that 1978 would see an increase of 50%. The number of passengers had exceeded a quarter of a million in 1976 and in 1977 the figure was likely to be 369,000.

Sumburgh was being asked to handle 57,000 movements with 560,000 passengers in 1978. An airport worker told me:

'I think we might have just about been able to handle the extra flights and passengers had the work been distributed more evenly throughout the operational day. We were asking the oil companies to change some of rig crew changes to weekend days. Because the traffic always came in three peaks, every day from Monday to Friday. If the weather changed, which it often does here, then we were in the shit. The first peak was at 9am, that lasted for about an hour, with something landing or taking off about every three minutes. Then we had another peak from mid-day to about 2pm - that one was tough, it was a movement in less than three minutes and at times there would be one every two minutes. The last peak would be between 4pm and 5pm. That was a bit easier - unless there had been that bad weather I mentioned. The airlines wanted to make sure that their own operation wouldn't be affected the next day, and so they would break their necks to make sure that any remaining flights would make it to us. It was at those times that the apron and the terminal were pretty crowded. I would say that it went far beyond uncomfortable. The fact that we did cope at all was a measure of good-will and patience, and that was on all sides, pilots, airport staff, passengers and many others who were involved. We had been promised a £5 million investment in airport facilities, which was desperately needed. I remember in 1977 that the air traffic controllers were shuddering at the thought of the expected increase. Bearing in mind that prior to this, our airport had been used to handling perhaps one flight every hour or so. The whole infrastructure could not have coped with the increase, not safely anyway. A company called Costarc laid down 30,000 square feet of tarmac, and still there wasn't enough room for passengers to embark and disembark aircraft. When the new development came in, it was impressive. They extended the terminal, parts of which were only two years old anyway. They planned to knock down the fire station and a hanger, and they built a new taxi way for helicopters to access the runway. It was terrible though, the work wasn't going to be completed in time for these new flights even though planning permission had been put in at the start. The Civil Aviation Authority were having to stump up for the costs, but they were liable, by law, to be financially accountable and it turned out that their Highland division was in debt to almost £2 million, and these new developments were going to cost an additional £3 million. I was asked to attend meetings with the local council and the CAA to find a way to relieve the bottleneck and it was proposed that we re-open Scatsa Airport as well as Tingwall and Baltasound airfields. They also decided that they would transfer some of the helicopter services to Wick, which would mean that passengers arriving into Sumburgh would have to be ferried by coach before being ferried to the oil rig.'

The new base at Sumburgh would see the opening of an 'office' in the shape of the former airport fire station that had been closed as expansion took place. The new office would house a staff of 25. New 'on-shore' oil related activities would also see an upturn in the number flights Dan-Air would provide. The airline was being tight-lipped about new plans, but an aircraft was successfully landed on the new Flotta tarmac strip on Shetland. Flights were up by 45% and passengers up by 32%. More than 140,000 kilos of freight was carried, an increase of 29%.

In July, a fifth 748 was based at Aberdeen and it was announced that by the end of the year there would be eight based at Aberdeen and two at Sumburgh. Staff numbers had increased to 42 flying crew, 36 ground staff and 12 engineers.

A series of jet charter flights were carried out in 1977 from Aberdeen to Asturias in Spain. The flights would on behalf of drilling company IDC and be for crew changes on an oil rig off the coast of Spain. Commencing in October for three months, the fortnightly flights would be operated by Comet aircraft. Tees-Side Airport would also see charter flights for oil workers for the first time. This led to the appointment of a permanent oil superintendent, Robert Willis, to be based at Aberdeen. The first batch of ten stewardess began training in October, the girls, who had been recruited locally, started their training at Aberdeen College and Dan-Air's Aberdeen base.

The end of 1977 saw the airport closed for several days due to Norwegian fog that had descended on the Shetlands. Only one aircraft left the airport, a Dan-Air HS 748 taking Sullem Voe workers to Glasgow. Several flights were grounded with accommodation being provided by hotels on Shetland itself as well as the spare beds of many airport staff and residents who stepped forward to assist stranded oil workers. Air Ecosse had been formed in 1977 and had built up a fleet of four Bandeirante aircraft to join the swell of airlines plying for their share of available contracts. Dan-Air had a license to operate scheduled services from Aberdeen to Norway and wished to introduce an optional stop at Sumburgh, a plan that was rejected by the CAA.

In December, the problem of how to get 3,000 oil workers home for Christmas faced Dan-Air. The workers were based at the Sullem Voe terminal. Between Friday 16th and Thursday 22nd December a total of sixty flights were operated, and between January 6th and 12th, the same thing happened again - in reverse. Most of the workers would fly home to Glasgow or Belfast, but a substantial number would also be going to Aberdeen. The operation was to be handled at Aberdeen, but to help the airline cope - a village hall, four miles away from the terminal was taken over to handle check in. Any luggage would be stored on a coach and passengers were taken directly to the waiting airport. Details of numbers and weights had to be given by a temporary phone line. Staff from mainland airports were brought in, and the police provided extra officers to help with security.

Weather conditions at Sumburgh have been described as 'challenging' for pilots. Radar had been installed in late 1976, but fog caused problems for most airlines. The Meteorological Off did not have a presence there and to achieve real time weather forecasts, the local lighthouse keeper agreed to provide details of current weather conditions to pilots. A new runway had been opened in 1975 but could only be used by light aircraft with a maximum all up weight of 12,500 lbs. Captain Roberts in Command of HS-748 G-ARMW was given permission to use the new runway as he was only carrying one passenger on his charter. The new radar facilities would allow pilots to be talked down to just 300 feet instead of the previous 700 feet. This would permit more landings when fog and cloud were present.

The Brent region, comprising of several oil rigs, had in July 1978 - 20,000 aircraft movements, those few rigs in the North Sea had just 5,000 fewer movements than Heathrow! A fleet of Sikorsky helicopters took workers to aircraft at Sumburgh and the newly re-opened Scatsa Airport. The majority of whom would be flying with Dan-Air. Scatsa had undertaken a proving flight on 22nd of the month and just two days later a company HS 748 carried out the first commercial flight into the airport in 38 years.

Stephen Palmer who worked on oil rigs for three years told us:

'I flew into both Scatsa and Sumburgh, I preferred Sumburgh. I have been lowered from an oil rig on special cables in baskets to check electrics with icy rain and waves just below me. I have had snow lashing on while I have been a few feet over the North sea - so cold that you are only permitted to be there for a few minutes before coming up for a hot drink. But nothing compares to having to attempt to land at Scatsa in a gale and only managing it on the third attempt. That one flight terrified me, and I am not easily scared. I'd had a coffee on the flight, I'd done it so many times that I knew when the decent started. As we began to go down the weather changed in a flash. And this forty odd seater felt like a light aircraft. We were up and down and the wings were flapping. The engine made different sounds, so I said to the hostess; I that normal love? She said it was, given the conditions. I was crapping myself. But we carried on. I felt sick and got the bag out - fortunately I didn't use it. The hostess sat down and told us to secure everything. Just as we were about to touch down the bloody thing went up in the air again. Which didn't do any of us any good. The pilot said he was sorry and we would go around again. The same thing happened, only this time, I am sure the wing looked like it had hit the runway! So he comes back on the tannoy and says we were going to make one more attempt at landing. If this failed we would have to go back to Aberdeen. There's usually a fair bit of banter with oileys - but the plane was almost silent, apart from the whirring engines. We came down with a bit of a thud - but as soon as we slowed down the pilot came on and said he had to have firm landing, but that he was sorry. It was not Dan-Air's fault, and you have to admire the pilot. The one who impressed me the most was the hostess. She was doing paperwork as we were landing. Hats off to her!'

In 1979 a Hawker Siddeley 748 crashed into the sea after failing to get airborne from the runway at Sumburgh, the airline was exonerated in the inquiry that followed. You can read more about the incident on the timeline (scroll down to 1979)

The pace of Dan-Air's activity from Aberdeen grew over the next few years with major contracts being awarded from most major oil companies. By 1984 fourteen HS 748 aircraft were based at Aberdeen. In the short and mid term the prospects looked good for the airline, but helicopters had seen significant shifts with technology. Newer aircraft could reach oil rigs directly from Aberdeen. One oil company manager spoke of a meeting with Dan-Air board members.

'When I worked with Shell I enjoyed a great relationship with the Dan-Air people. I found them a competent set of hands. As a company we had been approached by an airline who had a helicopter division. They had sent us a brochure that was emblazoned 'We lead others follow' There was an introductory letter and the offer of a meeting. So I thought a bit out of the box and contacted my Dan-Air people who arranged for a meeting with a board member. Which I duly attended. I had taken the brochure along and suggested that Dan-Air might enter the helicopter arena, and by doing so, be in a position to offer both direct from the mainland to the rigs flights and to carry on with the regular flights into Sumburgh. I virtually guaranteed that the contract would go their way. I was not alone with my praise of Dan-Air - all of our operation could find no fault with theirs. The board member wouldn't hear of it. He dismissed it out of hand saying they were an airline, not a helicopter operator. I did venture to say that the air taxi company they had recently set up, that we were a regular client of - was not an airline as such either, and that it would be a solid business move. He again dismissed me. My final plea was to tell him how we were involved in different kinds of oil - from the stuff you put in your aircraft, to oil rigs, to refining oil - to actually having petrol stations! that seemed to peak his interest. He said he would discuss it at board level and get back to me. I offered to reach out to him with more details before that event and he said 'No thank you, I will do some research myself and get back to you.' - I never heard from him again!'

So successful was Dan-Air's oil supply division that a secondary 'mini airline' was formed in Scotland. - The subsidiary company - London Air Taxi (LAT) took delivery of a Cesna Citation jet before setting up a new division - LAT Aberdeen The aircraft which would be based at Aberdeen and would be handled by Dan-Air. It was the first time such an aircraft was based at the airport. The eight seat executive jet could cruise at 420 mph and was capable of flying from Aberdeen to North Africa. The jet was aimed at serving oil executives and senior personnel. Ian Woodley was sales co-ordinator - oil services for both Dan-Air and LAT said: 'We believe the aircraft will be successful on flights from Aberdeen to London and Paris. It has also been chartered for longer distance flights to Finland and Spain. We have already used the aircraft for demonstration flights for oil company executives and they are delighted with it. '

Scheduled services were introduced to connect Aberdeen directly with London. Texas was well known throughout the world for its oil connections and Dan-Air formed a partnership with British Caledonian who had direct flights to Houston from Gatwick. Dan-Air's own scheduled services into Gatwick were timed to allow for a connection.

Flights into Scatsa and Sumburgh were not limited to UK airports. Several were flown in and out of Bergen. The Norwegian city is only ten miles further from Sumburgh than Aberdeen! Some positions on oil workers had unique skills and their salaries reflected that. Jahn Kleveland was a Field Specialist working on surface pressure control, he told us:

'I had been working on Norwegian oil rigs for several years and basically, I was head hunted. I would work on a rig on an ad-hoc basis, which meant I could pick and chose when to work. The salary was very good. The Norwegians faced the same issue that British companies did. In that the rigs are some distance from an airport. We had longer range helicopters, which were fine in good weather. I have, on more than one occasion, travelled to a rig on a supply vessel. Once in particularly rough seas. When I worked for Shell I flew into Aberdeen and then to Sumburgh before getting on a helicopter. I was a bit of a trek. On one occasion I caught a scheduled flight into Newcastle with Dan-Air and then on another Dan-Air flight to Aberdeen before the flight to Sumburgh, and I complained. To have to catch three flights and a helicopter to get to a rig 180 odd miles from my home was too much. I was told that the bosses had sorted out a flight from Sumburgh direct to Bergen. I expected it to be a tiny aircraft, but was stunned to see a 748 waiting for me. I was the only passenger! The stewardess had to do the full safety demo for me, she made me lots of coffees and gave me a sandwich. It was very pleasant. She introduced me to the flight deck and I was invited to watch the landing from a little seat in the cockpit. A few weeks later I was called onto the same rig and told that I would have a charter flight with Dan-Air waiting. This time there were two of us. A medic and myself. I did several trips and usually there were maybe six or seven of us. We didn't get the best flight times. But that was explained as a result that our charters were extra and had to be fitted in around their existing schedule. From the airline's point of view, I don't suppose they cared that the aircraft had only a few people on it. They would be getting their money from Shell whether there was one on board or forty one. Shell needed people like me, so they were happy to pay I guess.'

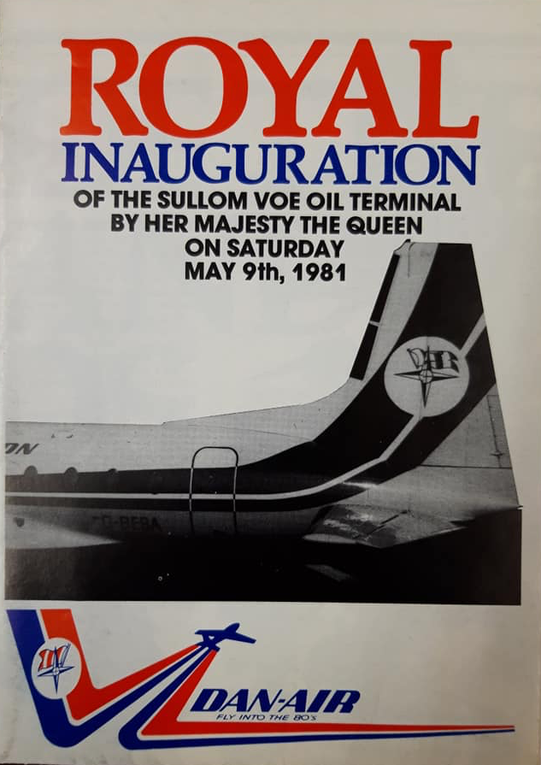

In May 1981 the Sullem Voe Oil Terminal was opened by the Queen. Dan-Air was selected to operate the accompanying press on a specially chartered Boeing 727 which would fly from Gatwick. The day was marred with a bomb that went off, which was believed to have been planted by the IRA. Many of the oil workers at Sullem Voe were Belfast people. Fortunately no-one was injured in the blast.

By 1983 the number of HS 748 aircraft used for oil supply charters had dwindled to just six models. The airline lost a contract to supply flights, to Alidair, the Scottish independent carrier. Dan-Air had said at the time that 'Although we are disappointed to have lost the contract, it is not the end of the world and we have several other contracts that have been renewed.'

The long-range helicopters that were now engaged in ferrying oil workers direct from the mainland onto oil rigs had taken away a lot of Dan-Air's oil charters. The airline had entered into a new phase of its operation, promising to concentrate on scheduled services to major business and leisure cities. The age of the HS 748 was also beginning to pose a problem. Some of the aircraft had reached the end of their flying hours and had to be phased out. One model, G-ARAY, one of the prototypes of the aircraft would be withdrawn from service in October 1989. Dan-Air said that the modifications to keep the 28 year old aircraft flying would be too expensive. In 1991 a contract renewal was offered to Dan-Air for a series of regular flights between Aberdeen and Scatsa, at a time when the remaining HS 748 aircraft were up for sale. Dan-Air turned the contract down. With an oil company manager telling us:

'I could not believe my ears. This was a good contract, but Dan-Air said they didn't have the right equipment for the flights. We later found out that no-one else did either. It would have made absolute sense to have leased in an aircraft just for this job, It would have been fully utilised. There was no question of it not being profitable had they done so, because even the 748 that we had used up until now had been profitable, so a newer, more efficient model would have been more so, the ATP was now available, which would have been ideal. Instead, we had to fall back on plan B, which was to contract Gill Air who would carry out the flights using a God awful Shorts 360 aircraft. That model was not up to standard at all. I'm sure it was technically proficient, but it had limitations in almost every sphere. It couldn't take of land in adverse weather. It was slower, carried less people and Gill Air themselves had limited experience in this type of operation. They were in the hands of secondary handling agents, and thus had none of their own staff at the airport when difficulties arose. The use of that aircraft would mean that there would have to be twice as many flights to carry the same amount of people. It was most unsatisfactory. As it happened, it was to be a stop-gap. We would have time to negotiate something over the next six months. We didn't even bother to involve Dan-Air. Ultimately we sought the services of Bristow, who had the capability of operating from the mainland to the rigs. They had support in place as well. It was a sad end to a very well regarded partnership. In later years Loganair and Stobart Air started scheduled services to Sumburgh, and that would mean where we needed fixed wing flights to the mainland, they were readily available. It would have been much nicer if Dan-Air had been around still to engage in these flights. But alas, it was not meant to be.'

Dan-Air's long time oil supply division was worthy of a section of its own on this website.

FOLLOW THESE LINKS

DISCUSS THIS SUBJECT

0

reviews